The characteristics we seek in selecting ventures aren’t surprising: We look at 1) potential for impact, 2) scalability, 3) caliber of the team, and 4) fit with our values and offering. But over the years, we’ve refined how we evaluate entrepreneurs for each of these characteristics. Here’s how we’re planning on doing it this year:

1. Potential for Impact

When we assess an entrepreneur’s potential for impact, we want to know two things: are you tackling a BFP and are you able to create profound impact?

Tackling a BFP: Are you tackling a big f*cking problem, a problem that seems impossible to solve and that urgently needs to be addressed? We’re talking about problems that affect one billion people—problems that no one knows how to overcome yet.

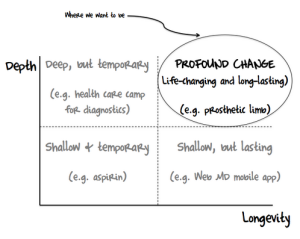

Able to create profound impact: Can you create profound impact? To us, this means you create DEEP and LASTING change for your customers or beneficiaries. For example, there’s value to health camps that provide medical diagnostics, but without follow-up treatment, their impact doesn’t last. Likewise, mobile phone apps that track health can create lasting value if used regularly, but rarely truly transform people’s health. We are interested in ventures that, for example, provide prosthetic limbs. That’s life-changing impact that lasts.

We’re talking about problems that affect one billion people—problems that no one knows how to overcome yet. Tweet This Quote

2. Scalability

Once we are confident that an entrepreneur is able to create profound impact in tackling a BFP, we want to know if they can create that impact at scale, reaching at least a million people. We assess their ability to scale by looking for two indicators: a convincing path to the impossible and the ability to scale revenue and impact together.

A convincing path to the impossible: Last year, we interviewed Rising Tide Car Wash, a company that employs people with autism to wash cars. Going into their interview, we were skeptical. A car wash? How much impact could these guys create? But as we listened to Rising Tide’s co-founders (Tom and John D’Eri), we realized a few things:

- These guys had a big objective: to make autism a competitive advantage in the job market. We respected the lofty goal, but saw no path to it… until they started telling us how they were going to get there.

- These guys knew the problem inside and out. They understood why people with autism weren’t getting jobs. They also knew that many people with autism perform focused, detail-oriented tasks extremely well, even if they have to do them over and over again.

- They knew that no brand has been successful in earning the loyalty of customers in the car wash industry (including NASCAR). They felt that the car wash industry was a place where they could employ people with autism to deliver a better quality product that would earn brand loyalty and lead to better business.

- They had evidence for this hypothesis. Their small team, employing 30 people with autism to wash cars, was outperforming the previous management of the car wash they took over by 2x in monthly revenue.

- They explained that they weren’t going to stop there. By validating that employing people with autism could learn to higher earnings for businesses, they planned to bring the model to other highly routinized industries, creating a movement that could provide jobs for thousands more people with autism.

After speaking with them, we found ourselves thinking, “This could actually work.” We want every entrepreneur we work with to walk us through this process: give us a big hairy audacious goal that seems impossible to achieve and then make us believe they can actually get there by demonstrating a deep understanding of the problem and a logical intervention to overcome it.

Revenues and impact scale together: Every venture that we look at has a way to create impact—an impact model—and a way to make money—a business model. The ventures that scale easiest have a heavy overlap between the two models, meaning that every dollar they earn creates more impact. A great example is 2013 Unreasonable venture MANA Nutrition, which manufacturers nutrient-enriched peanut butter that can cure kids of severe acute malnutrition. Every sale MANA makes leads to children gaining access to critical, life-saving nutrients. For MANA, more money equals more impact. And it’s working. MANA earned over $12 million in revenue last year and has cured one million kids of severe acute malnutrition.

For MANA, more money equals more impact. Tweet This Quote

By comparison, let’s look at Tom’s Shoes. Tom’s creates impact by giving away a pair of shoes for every pair of shoes it sells. The business model and impact model are essentially at odds with each other—giving away shoes eats into potential profits. When this conflict between business model and impact model exists, what choice might the company make if it runs into trouble? If forced to pick between one or the other, in most cases the company has to serve its business model in order to survive. We’re looking for ventures like MANA.

3. Team

We have learned that people are more important than ideas. The best ideas won’t change the world if the right people aren’t executing them.

Cohesion: According to Noam Wesserman, Harvard Business professor and author, 65 percent of high-potential startups fail due to co-founder conflict. And indeed, of the 12 Unreasonable Ventures that have closed their doors to date, most of them shut down due to co-founder conflict. So finding teams that will stick together through thick and thin is vital to us. We try to understand cohesion in three ways:

- Do co-founders share the same vision for the company?

- Can co-founders have extremely difficult conversations with each other, time and again?

- Do co-founders actively listen to one another and seek each other’s input?

The best ideas won’t change the world if the right people aren’t executing them. Tweet This Quote

To quote Paul Graham: “Startups do to the relationship between founders what a dog does to a sock: If it can be pulled apart, it will be.” We want co-founders who can’t be pulled apart.

Expertise: In our experience, the most successful founding teams know and deeply understand the problem they’re trying to solve—because they’ve lived it, they’ve worked in the industry for years, and they’ve spent a lot of time with their customers. This expertise is evident in every Unreasonable venture that’s experienced significant growth:

- Eneza, a mobile “Khan Academy” for students in rural Kenya, has grown from 40,000 to 350,000 users in the past year. It was founded by Toni Maraviglia, a teacher who has taught in both the U.S. and Kenya, and Kago Kagichiri, an experienced coder.

- Pivot (formerly Waste Enterprisers), which converts human waste into a fuel replacing coal in Kenya and recently closed $2.2 million in funding, was started by Ashley Muspratt. Before founding Pivot, she earned a PhD in waste management systems and consulted for the Gates Foundation on sanitation and waste.

- BioSense makes the ToucHb, a device that diagnoses anemia by shining light through a fingernail. It was started by Myshkin Ingawale, a former MIT researcher and electrical engineer, and Abhishek Sen, a former doctor who worked in rural clinics in India.

Formidability: Entrepreneurship is unforgivingly hard. But the most effective entrepreneurs we know get results anyway. They don’t make excuses or point out constraints. They take responsibility and find a way to get things done.

- 2011 Unreasonable Fellow Moses Sanga started his venture, EcoFuel Africa, with just $500. Now the company reaches over 100,000 people and earns over $1.2 million in annual revenue.

- Myshkin Ingawale and the team at BioSense built 32 versions of ToucHb and it failed every time… until their 33rd iteration. Now the WHO calls it one of the seven most innovative up-and-coming health care technologies in the world.

- 2010 Unreasonable Fellow Ben Lyon was turned down for investment over 100 times before he finally raised $1.2 million, led by Khosla Impact Fund.

The odds are against entrepreneurs. But the ones we’re looking for find a way.

The most successful founding teams know and deeply understand the problem they’re trying to solve Tweet This Quote

4. Fit with Unreasonable.

We’re not for everybody. We look for entrepreneurs with integrity, self-awareness, and coachability.

Integrity: Entrepreneurs deal in trust. In order to convince teammates, mentors, funders, and partners to invest in them and their idea, they need to be honest about their intentions and transparent about the challenges they face. We don’t accept entrepreneurs who bullshit us about what they do and don’t know (which happens every year in our interviews). We take entrepreneurs who are refreshingly and proactively truthful.

Self-awareness: We seek entrepreneurs who can articulate what they need to take their venture to the next level. We want to make sure that Unreasonable can address those needs.

Entrepreneurs by nature defy rules Tweet This Quote

Coachability: As Dwight D. Eisenhower said, “No plan survives contact with the enemy.” No matter how well-considered an entrepreneur’s approach, it’s likely to change based on feedback from mentors and the market. We seek entrepreneurs who understand that doing what works is more important than being right, and who are willing to change course if that’s what it takes to achieve their mission.

Selecting promising entrepreneurs is not a science. The process we’ve articulated above is at best a hypothesis, and one that we continue to test and refine. After all, entrepreneurs by nature defy rules. And we’re looking for the best of them right now. Applications for the 2015 Institute are open!